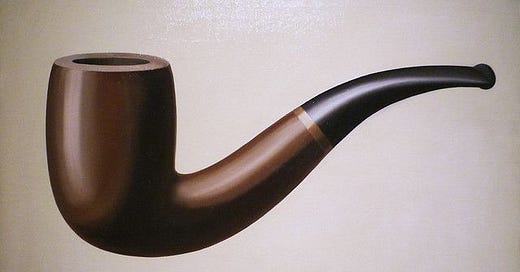

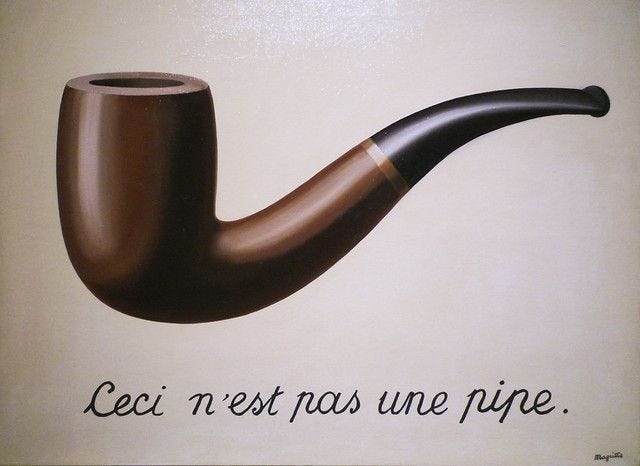

You’ve probably seen this painting before: René Magritte’s The Treachery of Images.

Unless you’ve never visited the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, you haven’t seen this painting; you’ve only seen a representation of it.

I can hear you groaning as you read that last sentence.

“YoU HaVeN'T ReAlLy sEeN ThAt pAiNtInG, YoU'Ve oNlY SeEn a rEpReSeNtAtIoN Of iT”

As silly and pedantic as that distinction may seem,1 it’s the essence of what the piece aims to express.

In the writing below the image—‘this is not a pipe’—Magritte questioned the relationship between the words we use, the symbols they represent, and the underlying reality they point to.

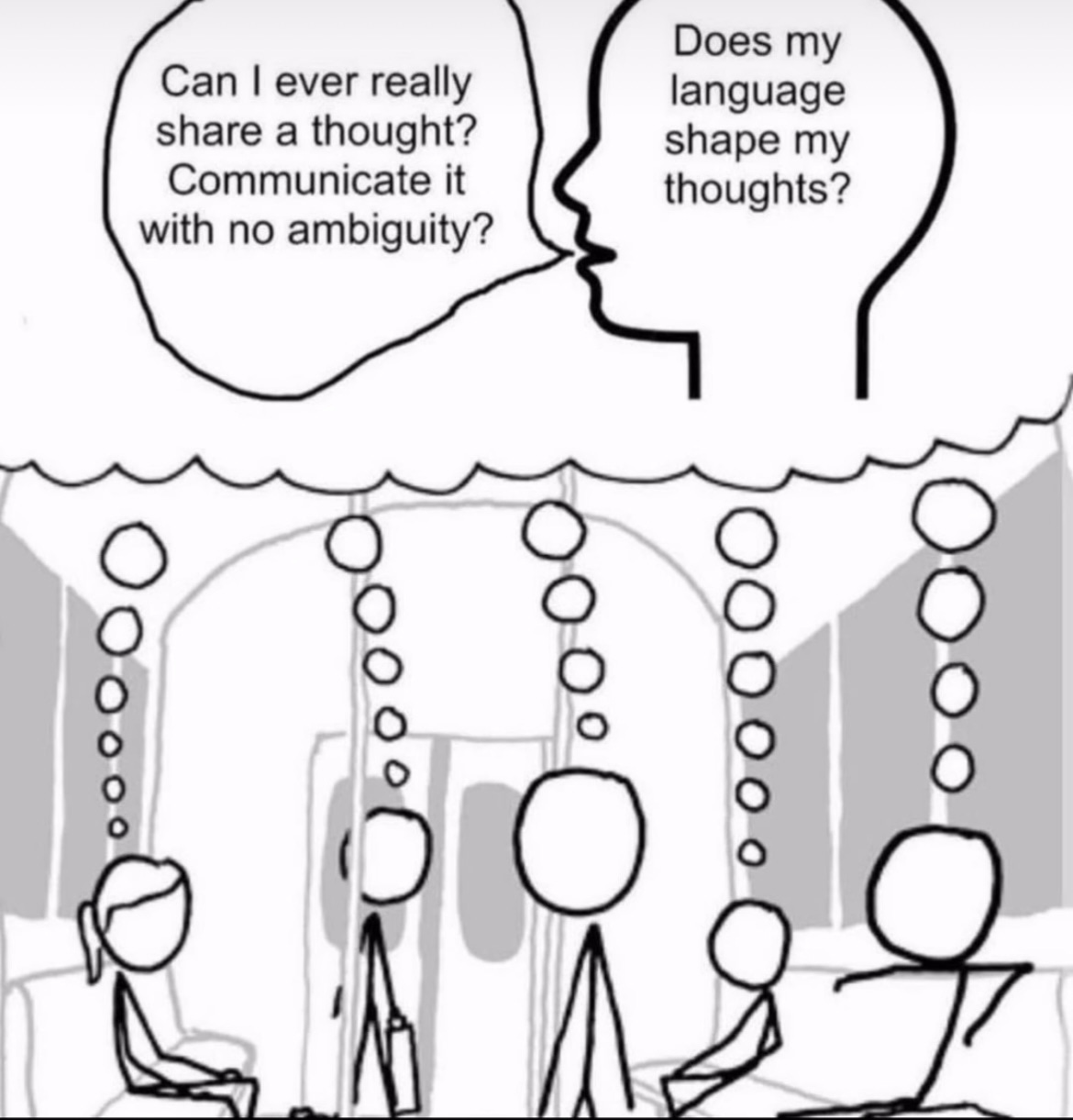

Too often, we assume that our interlocutors are using the exact same mental model of the world that we’re using. (And we all know what happens when you assume)2

So in order to meaningfully communicate, we need to:

Acknowledge our inherent subjectivity

Accept that there are limits to scientific knowledge

Understand the basic flaws in our communicative abilities

(basically we need to be okay not knowing anything)

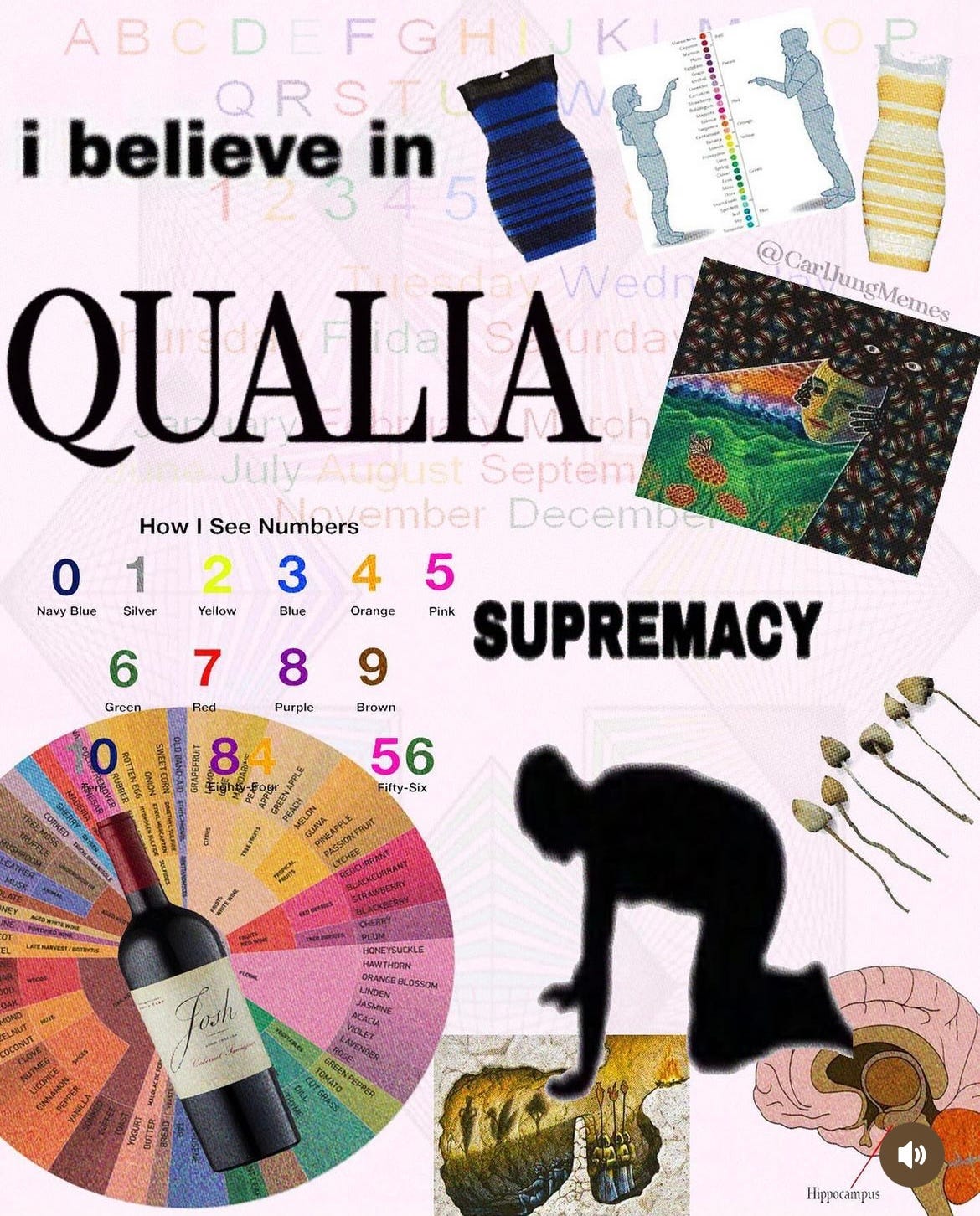

Qualia- the essence of subjective experience

I’ve always been fascinated by 'qualia,' a concept that is difficult to define but is well illustrated by Frank Jackson’s Knowledge Argument:

“The experiment describes Mary, a scientist who exists in a black-and-white world where she has extensive access to physical descriptions of color, but no actual perceptual experience of color. Mary has learned everything there is to learn about color, but she has never actually experienced it for herself. The central question of the thought experiment is whether Mary will gain new knowledge when she goes outside of the colorless world and experiences seeing in color.”

The answer to this question is difficult. Yes, by seeing color for the first time, Mary experienced something that she never had before, so obviously she learned SOMETHING. But what exactly did she learn?

Philosophers call these instances of objective, conscious experience qualia: the pain of a headache, the sweetness of honey, or the scent that unexpectedly revives a childhood memory.

Qualia are hard to explain because they encapsulate the essence of the ineffable.

But just like Justice Potter Stewart famously described obscenities: you know it when you see it.

THE PLURAL OF ANECDOTE IS (NOT) DATA

It’s often been said that the plural of anecdote isn’t data. Of course, relying on anecdote alone can lead to reporting bias, but all data gathered ultimately derives from a collection of individual observations.

The field of Natural Science focuses on predicting the occurrence of natural phenomena based on empirical data, while the field of Social Science (especially when using an anti-positivist approach) uses both quantitative and qualitative data.

While qualitative data seeks to measure the qualia of subjective experience, social experiments are notoriously difficult to replicate, a central issue of the replication crisis observed since the early 2010s.

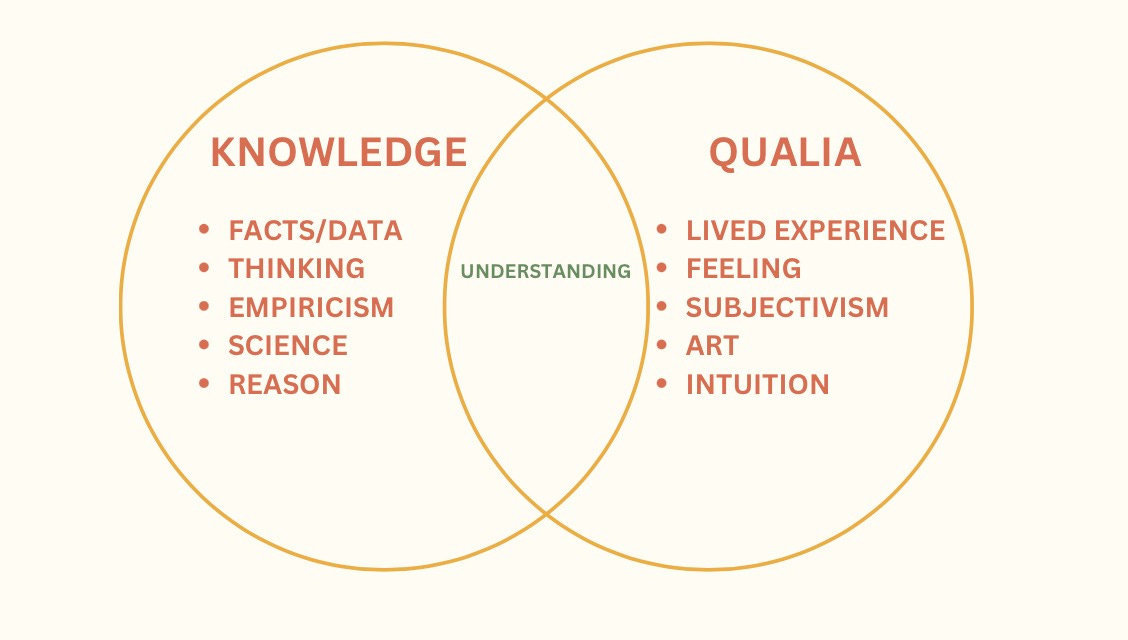

Understanding

I’d like to use this dichotomy of empirical data and subjective qualia to help us draw a distinction between knowing and understanding.

Before experiencing color, Mary may have had an encyclopedic repository of knowledge regarding color theory, but until she experienced it for herself, she didn’t have an understanding.

To know is to distinguish, differentiate, categorize, and separate. To understand is to connect and unify.

The Zen Buddhist metaphor of the moon and the pointing finger captures this difference beautifully. If someone points to the moon, the goal is for you to look at the moon, not fixate on the finger. To truly understand, you must look beyond the pointer (or symbol) to grasp the reality it indicates.

ChatGPT, Wolfram Alpha, and Wikipedia know a great deal, but they don’t understand. Lacking experiential frameworks, they interpret the world as a sea of literal symbols.

The word understand comes from the Old English under, derived from Proto-Indo-European *nter- "between, among"; and the Old English stand meaning “to exist in”.

Understanding then, is revealed through the synthesis of knowledge and qualia— the ineffable, subjective experiences that bridge the gap between the map and the territory.

We’ve all struggled to grasp a concept—studying, but just not getting it. Then, as soon as your focus drifts to something else, inspiration strikes. The lightbulb goes off above your head and you want to yell “eureka!”3

Understanding conveys a sentiment of awe, wonder, humility, and oneness.

Everything is a translation

The knowledge/understanding dichotomy explains why we still rely on human translators rather than computerized ones.

I used to think of translation as an exact science. You take a word in one language, you locate the equivalent in another language, and ta-da! you’ve just translated it.

But translation is a much more complicated process that involves not only an extensive vocabulary, but an understanding of nuanced implication in both the source language and the target language. Hence, a good translator is not only bilingual, but bicultural.

This is further complicated when you account for regional slang, registers, accents, euphemisms, technical jargon, context, double entendre, ambiguity, and the numerous other ways that meaning can be misconstrued.

An example of this is the different ways you ‘pay attention’ in different languages. In English, attention has a transactional connotation—it’s treated as a commodity. In Spanish, you prestar atención, or lend it. In German, you Aufmerksamkeit schenken, or gift it.

These subtle linguistic differences shape how speakers of each language conceptualize attention itself, proving that translation is more than finding equivalent words—it’s about understanding the worldview they encode.

Recognizing the intricacies of translation reveals that it isn’t limited to interlingual communication—it’s a fundamental aspect of all interpersonal communication.

If we look at the etymology of translate, it originates with the Latin: translatus meaning “carried over”.

Everything we say is an attempt to translate, or “carry over” our own ineffable experience to the minds of those we’re speaking with.

There’s another word with a nearly identical etymology originating from Greek rather than Latin:

*Metaphor*

The Map is not the territory

Metaphor, when recognized as such, is the truest form of communication, symbolizing truth without the pretense of exactitude.

When mistaken for reality, however, it can be harmful, misleading, and even deadly.

Remember Mary, the color scientist? Let’s imagine she works with several other people living in the same colorless world as her. After seeing such a beautiful manifestation of the visual spectrum, she excitedly attempts to convey to her colorblind colleagues the ineffable majesty of what she witnessed. How would she do this?

She would attempt to translate the experience into something they can understand. She might compare the color red to the pain of touching a hot stove, or the color blue to a cool drink of water.

Now imagine another colleague who has had a similar chromatic manifestation refutes her and describes red as a cool, soft rose petal, and blue as the heat from the bottom of a flame.

Is one of them mistaken? Which metaphor is more accurate? Which scientist is the authority on the qualia of color?

I’m sure you can see where this metaphor about metaphors (a meta-metaphor?) is headed.4

It’s (s)ubjective

I’m not arguing against the existence of an objective reality or even objective truth here. I would like to ask 1. can objective reality be known? and 2. can objective reality be objectively communicated?

These questions are my attempt to reconcile seemingly mutually exclusive beliefs, experiences, and opinions held by some of my closest friends, family members, and other very intelligent people I’ve met throughout my life.

Today’s cultural discourse often reduces complex ideas to pithy platitudes by attempting to posit them as inarguable fact and discredit any rebuttals. Two that come to mind are the liberal5: ‘In this house, we believe science is real,’ and the conservative: ‘Facts don’t care about your feelings’6— Both are ultimately trite, banal, cultural identity markers that don’t convey any real information other than: ‘The things I believe are true and verifiable, and you’re stupid if you don’t agree.’

Science isn’t a set of facts, but a methodology used to analyze data and eliminate false hypothoses. Spirituality can be a complementary methodology for analyzing the qualia of consciousness.

Many people are too hasty in their acceptance of any new study emerging from nascent fields. This lack of skepticism is antithetical to scientific inquiry. As Richard Feynman put it: “Science is the belief in the ignorance of experts.”

Others are too quick to judge their spiritual, mystical, transcendental, or otherwise powerful personal experiences as literal fact rather than through a metaphorical lens which can lead to the same legalistic or “letter of the law” approach criticized by Jesus Christ.7

In both cases, we are using our presupposed worldview in order to justify our beliefs. So how do we avoid doing this? By calling a spade a spade, while recognizing that everyone has a slightly different conceptualization of what a spade is.

Ceci pourrait être une pipe

I love the poem by the Zen monk Ryōkan that expresses the importance of not discounting our expressions of reality as lesser than reality itself, but recognizing both reality and expression as two essential components of the real:

“If we really see the moon, we see that the finger is a part of the moon. It’s not that the moon is reality and the finger is not. The finger, or the words we use, are part of reality. To distinguish between reality and the verbal expression of reality creates two separate things and makes reality itself more important than its expression using words.”

It’s often said that we fear what we don’t understand, but I don’t believe that’s true by default. We only fear the unknown when we judge it as negative.

Just as Magritte’s painting and the moon metaphor challenge us to question the link between expression and reality, Ryōkan’s poem reminds us to honor both the reality we see and the expressions we use to convey it. Approaching the unknown with humble curiosity transforms fear into wonder—and wonder into true understanding.

I’ve been known to be silly but I draw a firm line at pedantry

This is an ironic reference the modern proverb: “to assume makes an ass out of u and me” but I’m including this self-aware footnote to save both our asses

or as I like to say: “urethra!” when I want to pepper in some ribaldry

I’m actually not sure (I could assume that our minds are on the same wavelength here but I could easily be mistaken {see footnote 2}) so at risk of belaboring the point, I’ll finish explaining

I’m referring to the colloquial american usage of liberalism here

coined by conservative political commentator Ben Shapiro

see the parable of the good samaritan (Luke 10:25–37)

Fantastic read. Excited to revisit and digest slowly a second time through. Great work as always my friend!