I hate the first question I’m asked when I’m introduced to someone: “what do you do?”

I dread having to answer it because:

1. I don’t want my identity to be reduced to my job

2. I want to accurately communicate what it is I actually do1

The answer most people are looking for is that I’m a social media influencer, but I think that’s a bit of a misnomer.

Not the influencer part- that’s what I do for a living. I make money influencing people to buy stuff.2

I just don’t know that we can still get away with calling these platforms social.

Their original use case as tools for facilitating social interaction has evolved into a constant stream of advertisers, entertainers, and celebrities all vying for our very limited attention.

Our ability to maintain fulfilling friendships and real life community hinges on us recognizing these platforms for what they are, and prioritizing reality over the virtual world.

how many friends can you have?

The internet has globalized our social reach.

In the 1900’s most people had a relatively contained circle of influence, but with the advent of facebook in the 2010’s, we gained instant access to the majority of people on the planet.

You can’t have 8 billion friends though.

According to anthropologist Robin Dunbar, you can only have 150.

In his book: “grooming, gossip, and the evolution of language” he suggests that humans have a cognitive limit on the number of people we can maintain stable social relationships with. This 150 person limit is known as “Dunbar’s number”

Now, how many instagram followers do you have?

I bet it’s more than 150- a lot more.

In fact, about 75% of users in the US have more than 1,000.

So for the majority of people, instagram functions at least in part as a stage to communicate with an audience rather than just a method of interacting with those we share a close personal relationship with.

The friend-to-friend interactions that we have traditionally associated with these platforms is still occurring in places like snapchat, group chats and finsta accounts, but this evolution of online spheres requires a radical reevaluation of what these platforms are for and how much time we spend creating and consuming content vs. fostering human connection.

levels of friendship

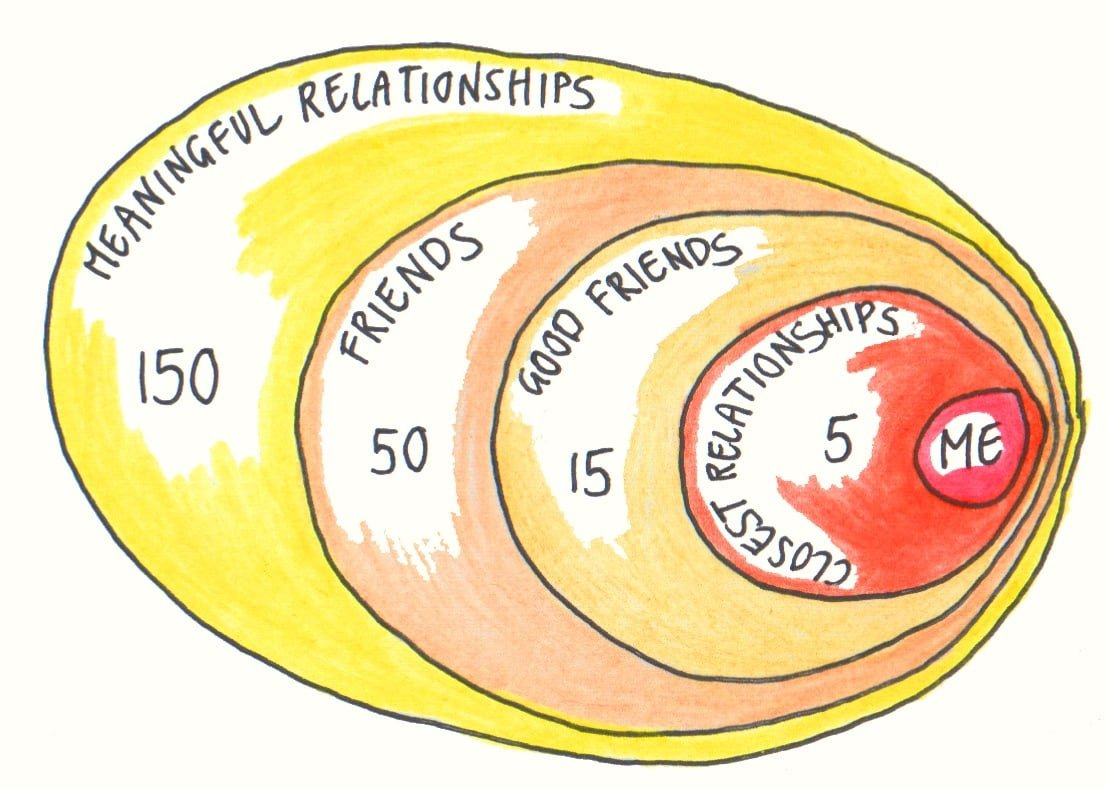

Within this limit of 150, there are varying levels of friendship3

closest relationships ~5

The first level are the five people closest to you- your besties. These are the people you interact with on a daily basis and are up to date on the intimate details of your life.

good friends ~15

In the second level are your good friends- your ride or dies. You probably interact with these friends on a regular basis and wouldn’t hesitate to invite them to hang out.

friends ~50

These are people who we would colloquially refer to as our friends. They would be in attendance if you were throwing a big social event like a birthday party or barbecue.

meaningful relationships ~150

When someone says: “I have a buddy who…” they’re probably referring to someone in this cohort. These people would turn up for a once in a lifetime event like your wedding or funeral.

friendship as a finite resource

Maintaining close friendships requires our time and attention. Friends mutually agree to support and listen to each other and to spend time together. There’s an opportunity cost to nurturing a friendship, so naturally we prioritize some people over others.

Social media has allowed us to automate a lot of the responsibility that accompanies friendship. Social media platforms have made friendship “convenient” but not necessarily fulfilling. It’s easy to “be friends” with someone without attending to the minutiae involved in fostering authentic connection.

the rise of the parasocial relationship

because our feeds contain a commingling of posts ranging from our closest confidants to massive celebrities, we can start to feel like we have a personal relationship with everyone we follow.

Relationships of this kind are called “parasocial relationships” or as I like to call them: “imaginary friends”

Parasocial relationships are the basic function of celebrity. Celebrities exist because a mass of people are invested in the existence of someone they have never met.

Each of these imaginary friendships comes at the cost of real friendship. Time spent learning about your favorite artist’s opinions, interests, and the intimate details of their lives is time not spent connecting with your friends and learning about their lives.

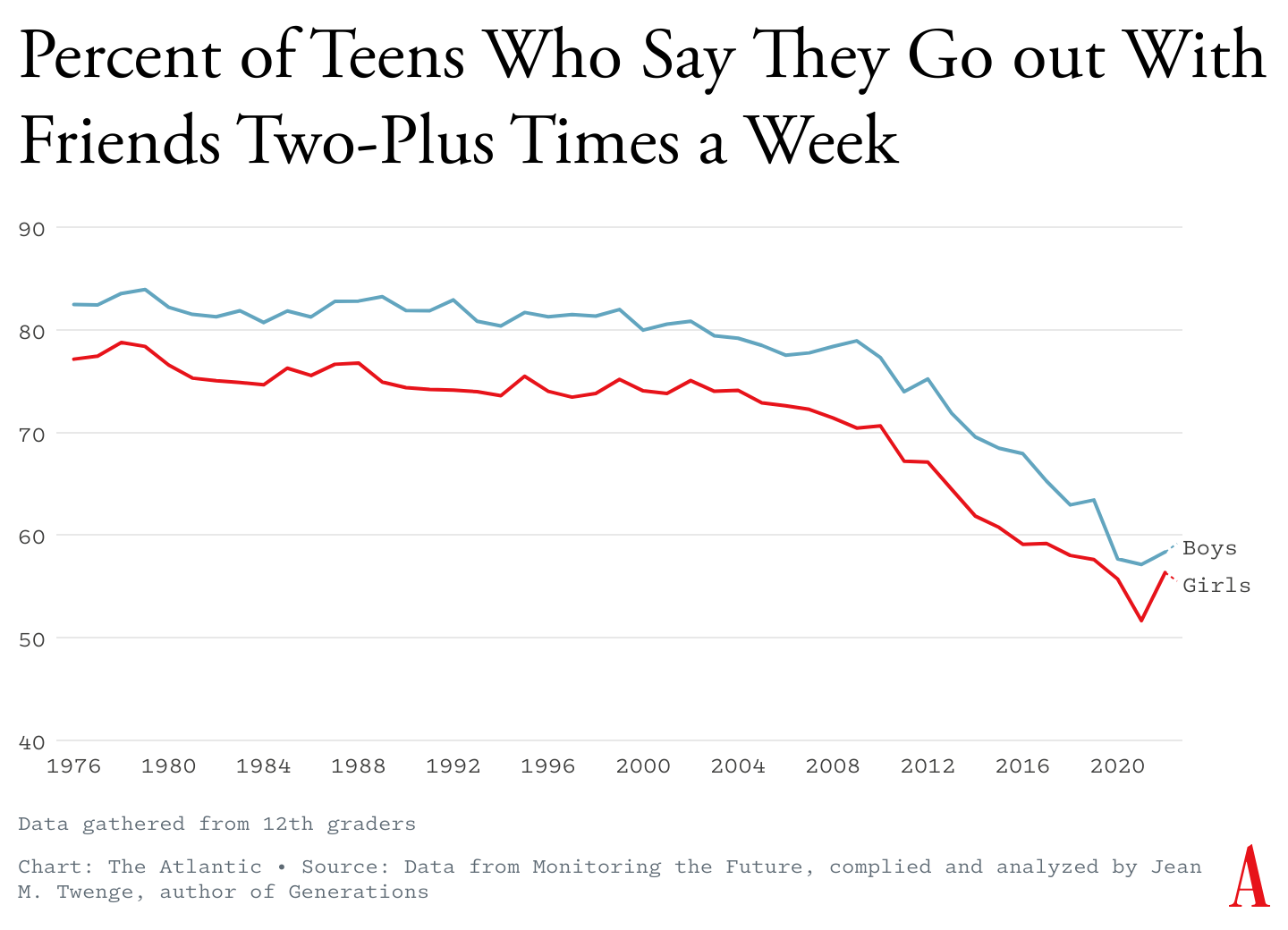

As our screentime increases, time spent hanging out with people who actually care about us is decreasing. Each of those 150 friendship slots is being replaced by people who don’t even know you exist.

We can see this happening in real time if we look at how often teens are hanging out with their friends. There’s a sharp decrease that correlates with the advent of social media platforms like instagram and facebook.

In the current age of social media, where everyone has an audience, the line has been blurred as to where friendship ends and celebrity begins. As a result, many are becoming parasocially attached to real life friends.

This has begun to bleed out of the sphere of the metaverse and into daily life. Not only do you have to be cognizant of how you’re being perceived by those who you’re with, but when someone is filming or taking pictures for social media, we’re all acutely aware of the potential audience that it will be delivered to.

the age of the online telemarketer

An influencer’s job is twofold: to maintain your attention, and to sell to you.4

Sometimes this is obvious- we know we’re being sold to when someone posts an ad or a link to the TikTok shop , but a lot of “influencing” occurs in more subtle ways.

Our attention is increasingly becoming our most valuable commodity and we’re giving it away for free to corporations at the steep cost of many of our relationships.

This doesn’t necessarily mean that an influencer doesn’t care about their audience or want them to benefit from what they’re selling; but it needs to be seen for what it is, and that is not friendship.

the loneliness epidemic

Americans are becoming increasingly polarized, atomized, and lonely.

Many factors are contributing to this- The decline in religiosity, the disappearance of third places, and the prevalence of car-centric infrastructure to name just a few.5

But one of the most pernicious is rooted in the way we approach the internet.

This scene from the movie “The End of the Tour” depicts David Foster Wallace talking about the addictive capacity of imaginary relationships:

In a time where you can live your entire life without leaving the house (estimates suggest that over half a million Japanese youth have become Hikimori), we need to be cognizant of what factors are keeping us socially isolated, and make efforts to combat them.

One improvement we could make is by better delineating the roles that are played by individuals we interact with in online spaces, and by prioritizing the relationships that matter to us rather than letting them be dictated by an algorithm.

Our attention is our most valuable commodity. It can also be our most valuable tool when it comes to solving these problems.

“Attention is the rarest and purest form of generosity.” -Simone Weil

We can start by paying attention to what we spend our time focusing on,6 so that rather than continuing to fund corporate greed and the development of tools designed to addict, we can grow real community with our friends, family, and neighbors.

I rarely answer the same way twice but my responses vary from: artist, digital marketer, videographer, content creator, writer, travel vlogger, philosopher, and unemployed friend (the line between self-employed and unemployed can be very fine sometimes)

I’ve spent a lot of energy debating the ethics of this with myself.

A fun exercise is to see if you can list all of your friends and categorize them in these bubbles.

I’m using the broader version of the term influencer here to include movie stars, music artists, authors, politicians, and anyone else who derives an income from their notoriety or social following.

I have future essays planned for all of these topics, so please let me know which ones you’d like me to deep dive.

This sort of “meta-attention” or paying attention to what we’re paying attention to is the key to taking control of one’s life rather than passively reacting to every latent impulse.

Thanks for reading! I’d love to hear your thoughts on how we can approach potential solutions to this problem!

My favorite part of this piece is that it quantifies human connection without taking the human-ness out of the explanation. Understanding that we exist in unspoken social structures and circles is essential. So much of the energy we expend in these realms is unavoidable (in my opinion) but I like the idea of being aware who we are giving our time and attention to. For example, yesterday I learned what 10 things Jerry Seinfeld can't live without on GQ's youtube channel, but I can't say I know what most of my friends consider their "essentials." Maybe I should ask them!