Algorithmic Oracles

The Deification of the Digital

“Modern men believe they have freed themselves from old dogmas. But what do they do? They bow before new ones! The party, the cause, the nation, the equality of all men—these become their new gods! And thus, they are more enslaved than before!”

—Friedrich Nietzsche, Beyond Good and Evil

Our increasingly secular world has created an ontological gap1—one now gradually filled by the ethos prescribed by the digital platforms we inhabit.

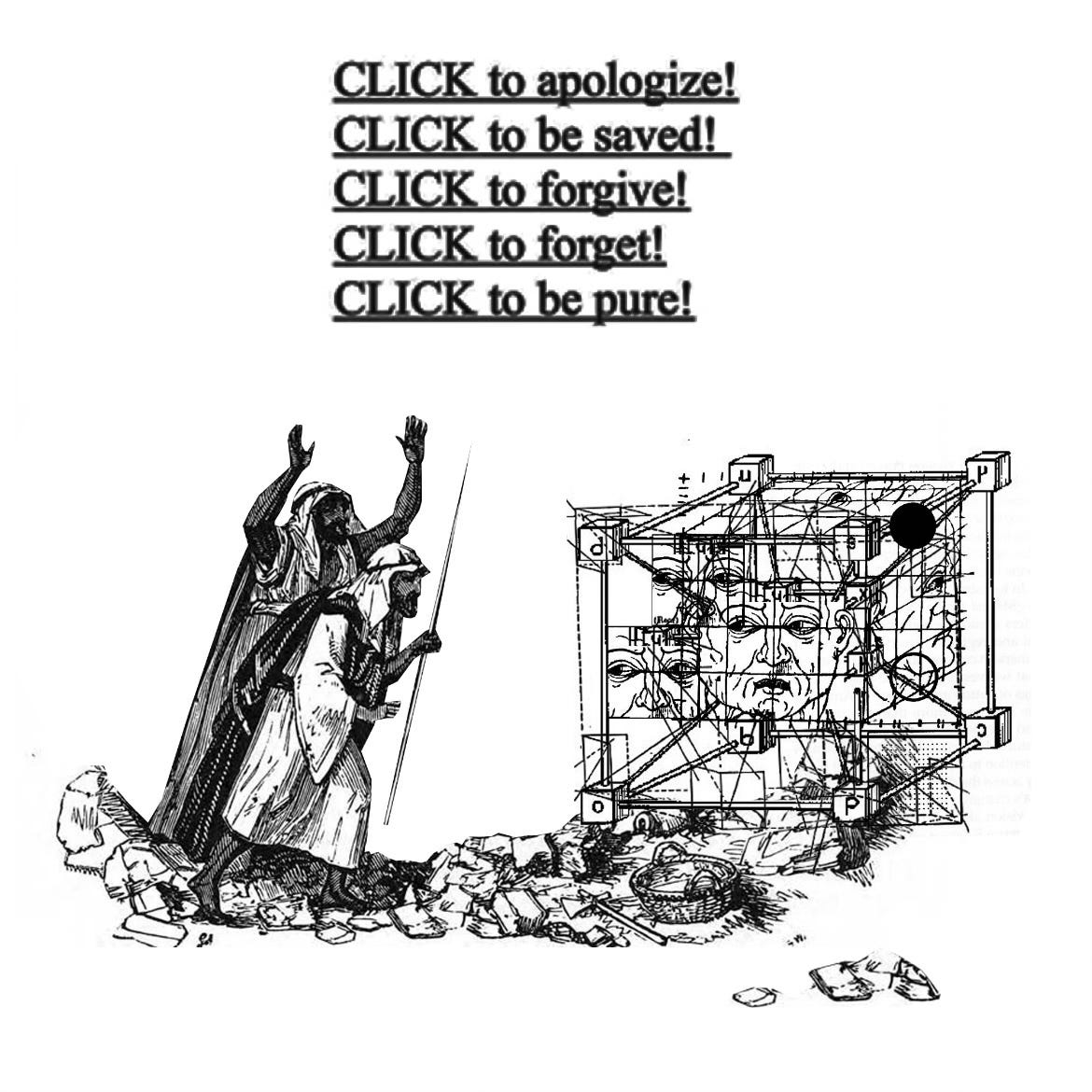

Each platform has its own variation, but the underlying theology remains the same:

“What appears is good; what is good appears.”2

This belief is rarely stated aloud. Yet, as we continue to inhabit spaces where the spectacle reigns, we either:

implicitly accept it, or

reject it, but feel powerless to resist.

In this way, we treat the algorithms that govern our digital lives as gods. We become digital Muslims—Muslim meaning, literally, “one who submits”3—to the will of these gods.

Discourse about online growth, especially in the short-form video space, drips with religious allusion. Creators speak of “appeasing the algorithm” or being “blessed by it,” the way a Canaanite farmer once sought favor from Yahweh.

“In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God.”

—John 1:1

God and language have always been inseparable. They are conceptual agreements—shared structures of value. You do not create language any more than you create God, but you can converse with both.

Philosopher Byung-Chul Han suggests that sacredness lies not just in language itself, but in how we attend to it. He writes:

“It is no coincidence that the word ‘religion’ comes from relegare, to focus the attention. All religious praxis is an exercise of attention… repetitions make the attention stabilize and deepen. Repetition is the essential feature of rituals.”4

To attend is to sanctify; to repeat is to canonize.

Myth, once passed through oral tradition—molded by and accessible to all who could listen and repeat— became fixed doctrine: guarded by priests, whose exegesis became law.

The priesthood persists, but its codification is now more literal.

The digital world is not merely enhanced by language—it is built from it.

What are computers, if not interpreters of scripture?5

The priestly class has been replaced by machines, doing the bidding of technocrats and the capital they serve.

We have been convinced that clicks, indeed, save.

The loss of shared metaphysical meaning or purpose in a post-religious age. This “gap” is increasingly filled by secular ideologies, technologies, or cultural systems offering implicit frameworks of belief.

Guy Debord, The Society of the Spectacle (1967), aphorism 12.

Debord’s work critiques modern society’s shift from lived experience to mediated representation. “The spectacle” supplants authenticity with appearance as a shared measure of value.

“Muslim” comes from the Arabic root س-ل-م (S-L-M), meaning peace, submission, or surrender.

Byung-Chul Han, The Disappearance of Ritual.

Han draws on Cicero’s lesser-known etymology of religion from relegare (to reread, return, or attend), as opposed to the more widely accepted derivation from religare (to bind).

From the Latin scriptura, meaning “writing” or “something written.”

Wow. I have been thinking about this concept a lot lately. What are we filling that gap with? As a society, we no longer have a shared "enchantment" of the world, and yet, the world seems to becoming more enchanted as AI enters our daily life. I recently read a book called "God Human Animal Machine" that absolutely blew me away. The author went to a Seminary to study biblical theology and ended up losing her faith and becoming obsessed with machines. The parallels she makes between religion and technology were incredible.

Life is loopy